In the complex ecosystem of industrial fluid handling, the diaphragm pump—specifically the Air-Operated Double Diaphragm (AODD) variant—is revered as the ultimate problem solver. Unlike centrifugal pumps that rely on high-speed impellers and mechanical seals, diaphragm pumps utilize a reciprocating action that is both gentle on the fluid and incredibly robust against harsh operating conditions. From the transfer of hazardous chemicals in pharmaceutical labs to the movement of abrasive slurries in heavy mining operations, the versatility of these pumps is unmatched. However, this versatility comes with a challenge: the vast array of material combinations and sizing options can make the selection process daunting. Choosing the wrong configuration can lead to frequent diaphragm ruptures, inefficient air consumption, and costly production halts.

The Mechanical Core: Understanding AODD Pump Dynamics and Advantages

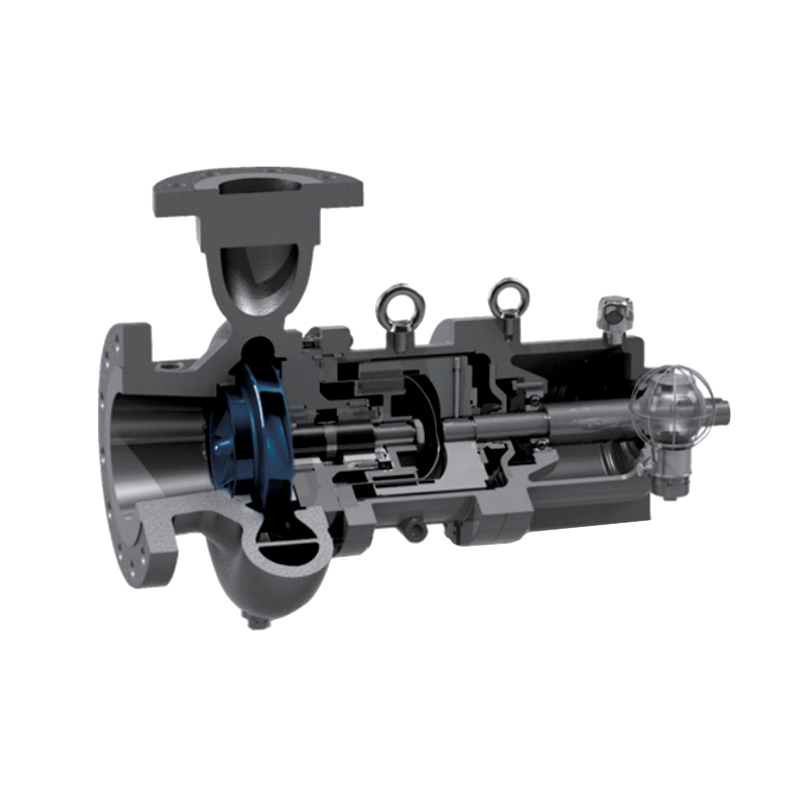

To select the right pump, one must first understand the unique mechanical advantages that diaphragm technology offers over other positive displacement or centrifugal designs. An AODD pump operates using a simple yet effective principle: compressed air is shifted from one chamber to another by an air distribution valve, moving two diaphragms back and forth. This creates a vacuum to draw fluid in and pressure to push it out. Because the pump is powered by air rather than an electric motor, it is inherently explosion-proof and ideal for ATEX-regulated environments.

Seal-less Design and Leak Protection

The most significant engineering advantage of a diaphragm pump is its seal-less construction. In traditional centrifugal pumps, the mechanical seal is the most common point of failure, especially when handling crystalline, abrasive, or highly corrosive fluids. A leak in a mechanical seal can lead to environmental contamination, loss of expensive product, and safety hazards for operators. Diaphragm pumps eliminate this risk entirely by using the diaphragms themselves as a static seal. This design ensures that the fluid being pumped is completely isolated from the atmosphere and the pump’s internal air mechanism. This makes them the primary choice for hazardous chemical transfer, where even a minor leak could result in a regulatory violation or a workplace injury. Furthermore, the absence of mechanical seals means there is no friction-generated heat at the seal face, allowing the pump to handle heat-sensitive fluids without degrading their chemical structure.

Dry Run and Self-Priming Capabilities

Operational flexibility is a key differentiator for AODD pumps. Most industrial pumps require “priming”—filling the pump casing with fluid before start-up—and can be severely damaged if they “run dry” (operate without fluid). Diaphragm pumps are fundamentally different. They are capable of dry self-priming, meaning they can create enough vacuum to pull fluid from a suction lift of several meters even when started dry. Additionally, if a tank runs empty, an AODD pump can continue to run on air indefinitely without the risk of overheating or internal galling. This is particularly valuable in sump drainage, tank stripping, and unloading applications where fluid levels are inconsistent. By selecting a pump with strong dry-run capabilities, industries reduce the need for complex float switches or dry-run protection sensors, simplifying the overall system architecture and reducing maintenance overhead.

Gentle Fluid Handling and Solids Passage

Many industrial fluids are “shear-sensitive,” meaning their physical properties change if they are subjected to high-velocity agitation. Products like fruit purees, specialized polymers, and certain oils can be ruined by the high-speed shearing action of an impeller. The reciprocating motion of a diaphragm pump is low-velocity and gentle, preserving the integrity of the fluid. Furthermore, the internal check valve system—typically using balls or flaps—allows for the passage of significant solids. In wastewater treatment or mining, pumps must move liquids containing stones, debris, or thick sludge. A 2-inch diaphragm pump can often pass solids up to 6mm or even 50mm depending on the valve design. This ability to handle high-viscosity and solids-laden fluids without clogging makes the diaphragm pump an essential tool for “dirty” industrial processes.

Operational Excellence: The STAMP Method for Professional Selection

In the pumping industry, the “STAMP” method is the professional gold standard for ensuring a pump is correctly specified. STAMP stands for Size, Temperature, Application, Material, and Pressure. By systematically evaluating each of these five factors, engineers can avoid the “misapplication” errors that account for over 80 percent of premature pump failures.

Material Compatibility: The Wetted Parts Strategy

The “Material” component of the STAMP method is arguably the most critical for long-term ROI. A diaphragm pump consists of two main categories of materials: the pump body (outer housing) and the wetted elastomers (diaphragms, balls, and seats).

- Housing Materials: For non-corrosive fluids like oils and solvents, Aluminum or Cast Iron housings offer a durable and cost-effective solution. However, for food-grade or pharmaceutical applications, 316 Stainless Steel is required to meet FDA and sanitary standards. For highly aggressive acids or bases, non-metallic housings like Polypropylene or PVDF (Kynar) are mandatory to prevent the housing itself from dissolving.

- Elastomer Selection: The diaphragms are the “beating heart” of the pump and are subjected to millions of flex cycles. PTFE (Teflon) offers near-universal chemical resistance but has a shorter flex life and requires a backup diaphragm. Santoprene or Buna-N offer excellent mechanical longevity for water-based slurries and oils but will fail rapidly if exposed to strong acids. Using a Chemical Compatibility Chart is essential; for example, pumping toluene with a Buna-N diaphragm will cause the elastomer to swell and rupture within hours. Matching the elastomer to the fluid’s pH, concentration, and temperature is the single most important step in preventing unplanned downtime.

Sizing and Air Consumption Efficiency

“Size” involves more than just matching the pipe diameter. It requires a balance between the desired flow rate (GPM) and the total dynamic head (TDH) the pump must overcome. A common mistake is selecting a small pump and running it at its maximum stroke rate to meet a production target. This results in high-frequency vibrations, increased noise levels, and a rapid decrease in the Mean Time Between Failures (MTBF).

- The 50 Percent Rule: For optimal efficiency, professional engineers recommend sizing a pump so that the required flow rate is achieved at approximately 50 percent of the pump’s maximum rated capacity. This “oversizing” allows the pump to run at a slower, more rhythmic pace, which dramatically extends the life of the diaphragms and the air valve.

- Energy Costs: Compressed air is an expensive utility. A pump that is poorly sized for its application will consume excessive amounts of air. Modern high-efficiency air distribution systems (ADS) are designed to prevent “over-filling” the air chambers, which can reduce air consumption by up to 40 percent. When selecting a pump, looking at the “Air Consumption vs. Flow” curve is vital for calculating the long-term energy impact on the facility’s air compressors.

Technical Comparison of Diaphragm Pump Materials

The following table serves as a quick-reference guide for matching pump materials with common industrial fluids and conditions.

| Housing/Elastomer | Chemical Resistance | Max Temperature | Primary Industry |

|---|---|---|---|

| Stainless Steel / PTFE | Very High (Universal) | 104°C | Pharma, Food, Bio-Tech |

| Polypropylene / Santoprene | High (Acids/Bases) | 66°C | Water Treatment, Plating |

| Aluminum / Buna-N | Moderate (Oils/Solvents) | 82°C | Automotive, Oil & Gas |

| PVDF / PTFE | Extreme (Concentrated Acid) | 107°C | Semiconductor, Chemical |

| Cast Iron / Neoprene | Moderate (Abrasives) | 93°C | Mining, Construction |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

What is the difference between a ball valve and a flap valve?

Ball valves are the standard for most liquids, offering a reliable seal and high efficiency. Flap valves are designed for fluids containing large or stringy solids (like rags or large stones) that would prevent a ball from seating properly.

Why is my diaphragm pump “stalling” or stopping mid-cycle?

Stalling is usually caused by two things: “icing” in the air exhaust or a dirty air valve. As compressed air expands, it cools rapidly, which can freeze moisture in the air line. Using an air dryer or an anti-ice muffler can solve this.

Can I use a diaphragm pump for high-viscosity liquids?

Yes. AODD pumps are excellent for viscous fluids like molasses or heavy polymers. However, you must slow down the stroke rate and use larger suction lines to allow the thick fluid time to enter the pump chambers without cavitating.

Technical References and Standards

- Hydraulic Institute (HI) 10.1-10.5: Air-Operated Pumps for Nomenclature, Definitions, Application, and Operation.

- ATEX Directive 2014/34/EU: Equipment and protective systems intended for use in potentially explosive atmospheres.

- FDA CFR 21.177: Indirect food additives: Polymers - Rubber articles intended for repeated use.

- ISO 9001:2015: Quality management systems for the manufacture of industrial pumping equipment.

English

English русский

русский عربى

عربى

.jpg)

ENG

ENG

TOP

TOP